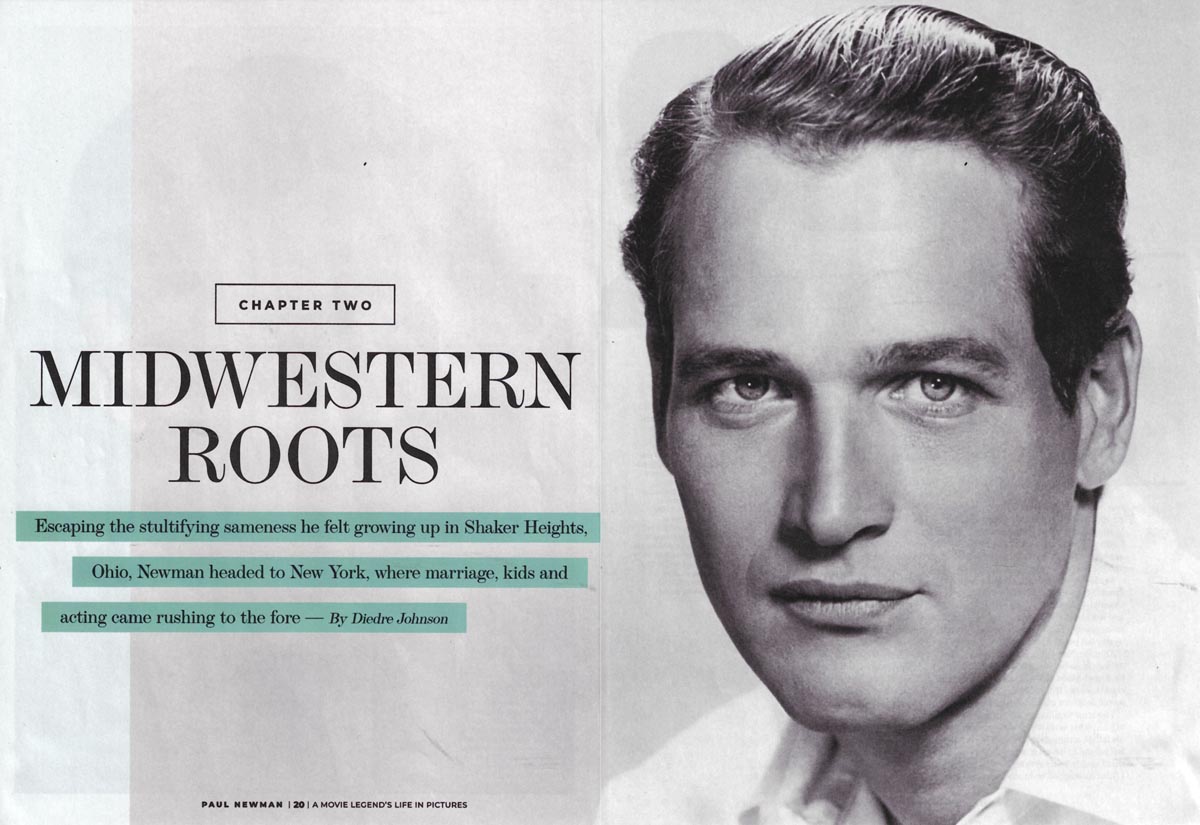

Part 1 Midwestern Roots

By Diedre Johnson

EVEN WHEN HE RECORDED HIMSELF reminiscing about his life with an aim to publish a memoir, Paul Newman could be painfully self-deprecating. “If I had to define ‘Newman’ in the dictionary, I’d say: ‘One who tries too hard,'” his transcript bears out in 2022’s Paul Newman: The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man: A Memoir.

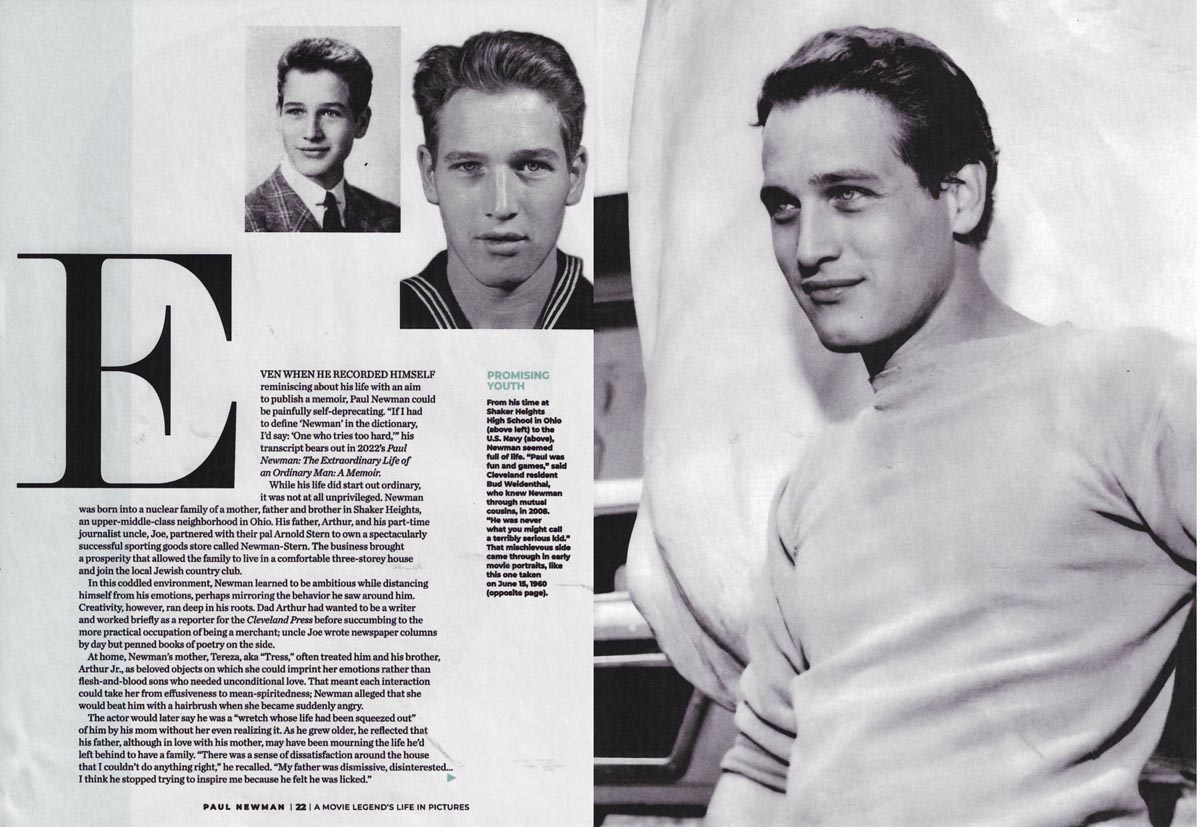

While his life did start out ordinary, it was not at all unprivileged. Newman was born into a nuclear family of a mother, father and brother in Shaker Heights, an upper-middle-class neighborhood in Ohio. His father, Arthur, and his part-time journalist uncle, Joe, partnered with their pal Arnold Stern to own a spectacularly successful sporting goods store called Newman-Stern. The business brought prosperity that allowed the family to live in a comfortable three-story house and join the local Jewish country club.

In this coddled environment, Newman learned to be ambitious while distancing himself from his emotions, perhaps mirroring the behavior he saw around him. Creativity, however, ran deep in his roots. Dad Arthur had wanted to be a writer and worked briefly as a reporter for the Cleveland Press before succumbing to the more practical occupation of being a merchant; Uncle Joe wrote newspaper columns by day but penned books of poetry on the side.

At home, Newman’s mother, Tereza, aka “Tress,” often treated him and his brother, Arthur Jr., as beloved objects on which she could imprint her emotions rather than flesh-and-blood sons who needed unconditional love. That meant each interaction could take her from effusiveness to mean-spiritedness; Newman alleged that she would beat him with a hairbrush when she became suddenly angry.

The actor would later say he was a “wretch whose life had been squeezed out” of him by his mom without her even realizing it. As he grew older, he reflected that his father, although in love with his mother, may have been mourning the life he’d left behind to have a family. “There was a sense of dissatisfaction around the house that I couldn’t do anything right,” he recalled. “My father was dismissive, disinterested… I think he stopped trying to inspire me because he felt he was licked.”

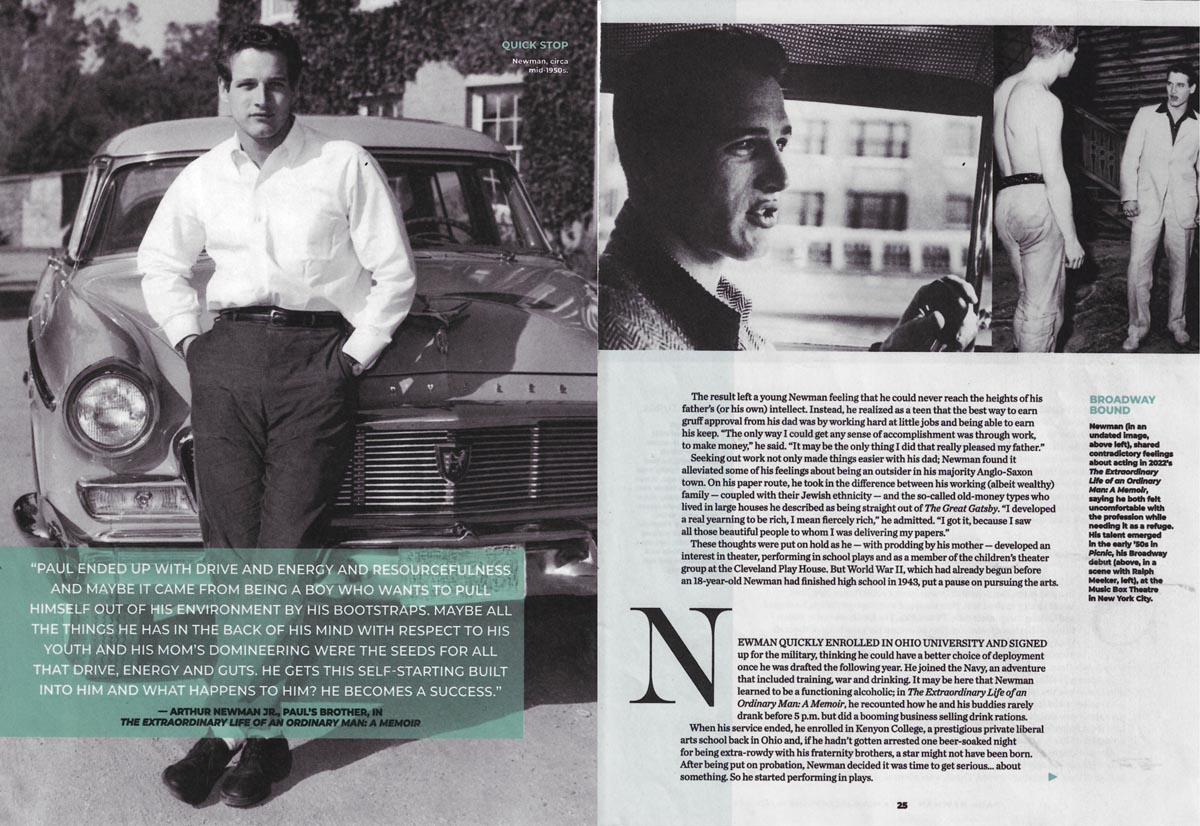

The result left a young Newman feeling that he could never reach the heights of his father’s (or his own) intellect. Instead, he realized as a teen that the best way to earn gruff approval from his dad was by working hard at little jobs and being able to earn his keep. “The only way I could get any sense of accomplishment was through work, to make money,” he said. “It may be the only thing I did that really pleased my father.”

Seeking out work not only made things easier with his dad; Newman found it alleviated some of his feelings about being an outsider in his majority Anglo-Saxon town. On his paper route, he took in the difference between his working (albeit wealthy) family — coupled with their Jewish ethnicity — and the so-called old-money types who lived in large houses he described as being straight out of The Great Gatsby. “I developed a real yearning to be rich, I mean fiercely rich,” he admitted. “I got it because I saw all those beautiful people to whom I was delivering my papers.”

These thoughts were put on hold as he — with prodding by his mother — developed an interest in theater, performing in school plays and as a member of the children’s theater group at the Cleveland Play House. But World War II, which had already begun before 18-year-old Newman had finished high school in 1943, put a pause on pursuing the arts.

NEWMAN QUICKLY ENROLLED IN OHIO UNIVERSITY AND SIGNED up for the military, thinking he could have a better choice of deployment once he was drafted the following year. He joined the Naw, an adventure that included training, war, and drinking. It may be here that Newman learned to be a functioning alcoholic; in The Extraordinary Life of an

Ordinary-Man: A Memoir, he recounted how he and his buddies rarely drank before 5 p.m. but did a booming business selling drink rations. When his service ended, he enrolled in Kenyon College, a prestigious private liberal arts school back in Ohio, and, if he hadn’t gotten arrested one beer-soaked night for being extra-rowdy with his fraternity brothers, a star might not have been born.

After being put on probation, Newman decided it was time to get serious… about something. So he started performing in plays.

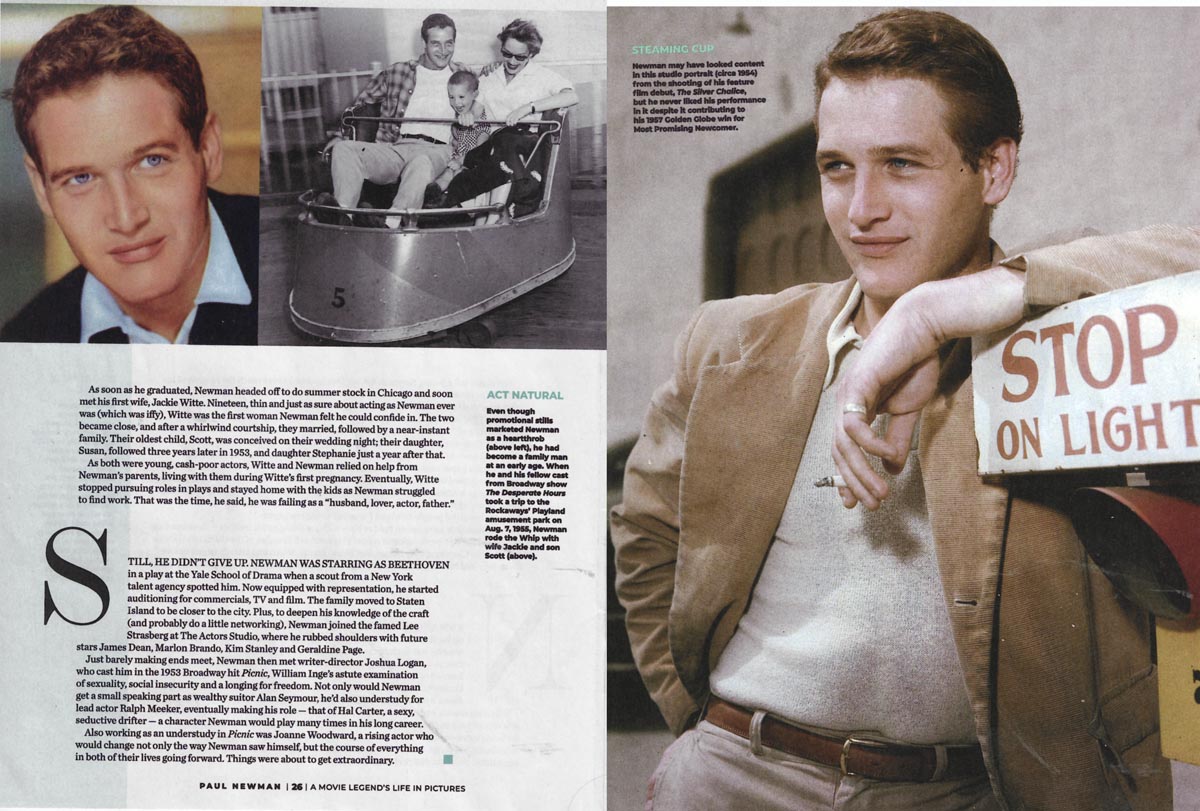

As soon as he graduated, Newman headed off to do summer stock in Chicago and soon met his first wife, Jackie Witte. Nineteen, thin and just as sure about acting as Newman ever was (which was Witte was the first woman Newman felt he could confide in. The two became close, and after a whirlwind courtship, they married, followed by a near-instant family. Their oldest child, Scott, was conceived on their wedding night; their daughter, Susan, followed three years later in 1953, and their daughter Stephanie just a year after that.

As both were young, cash-poor actors, Witte and Newman relied on help from Newman’s parents, living with them during Witte’s first pregnancy. Eventually, Witte stopped pursuing roles in plays and stayed home with the kids as Newman struggled to find work. That was the time, he said, he was failing as a “husband, lover, actor, father.”

STILL, HE DIDN’T GIVE UP. NEWMAN WAS STARRING AS BEETHOVEN in a play at the Yale School of Drama when a scout from a New York talent agency spotted him. Now equipped with representation, he started auditioning for commercials, TV, and film. The family moved to Staten Island to be closer to the city. Plus, to deepen his knowledge of the craft (and probably do a little networking), Newman joined the famed Lee Strasberg at The Actors Studio, where he rubbed shoulders with future stars James Dean, Marlon Brando, Kim Stanley, and Geraldine Page.

Just barely making ends meet, Newman then met writer-director Joshua Logan, who cast him in the 1953 Broadway hit Picnic, William Inge’s astute examination of sexuality, social insecurity, and a longing for freedom. Not only would Newman get a small speaking part as wealthy suitor Alan Seymour, he’d also understudy for lead actor Ralph Meeker, eventually making his role — that of Hal Carter, a sexy, seductive drifter — a character Newman would play many times in his long career.

Also working as an understudy in Picnic was Joanne Woodward, a rising actor who would change not only the way Newman saw himself, but the course of everything in both of their lives going forward. Things were about to get extraordinary.

Part II An Enduring Legend

By Diedre Johnson

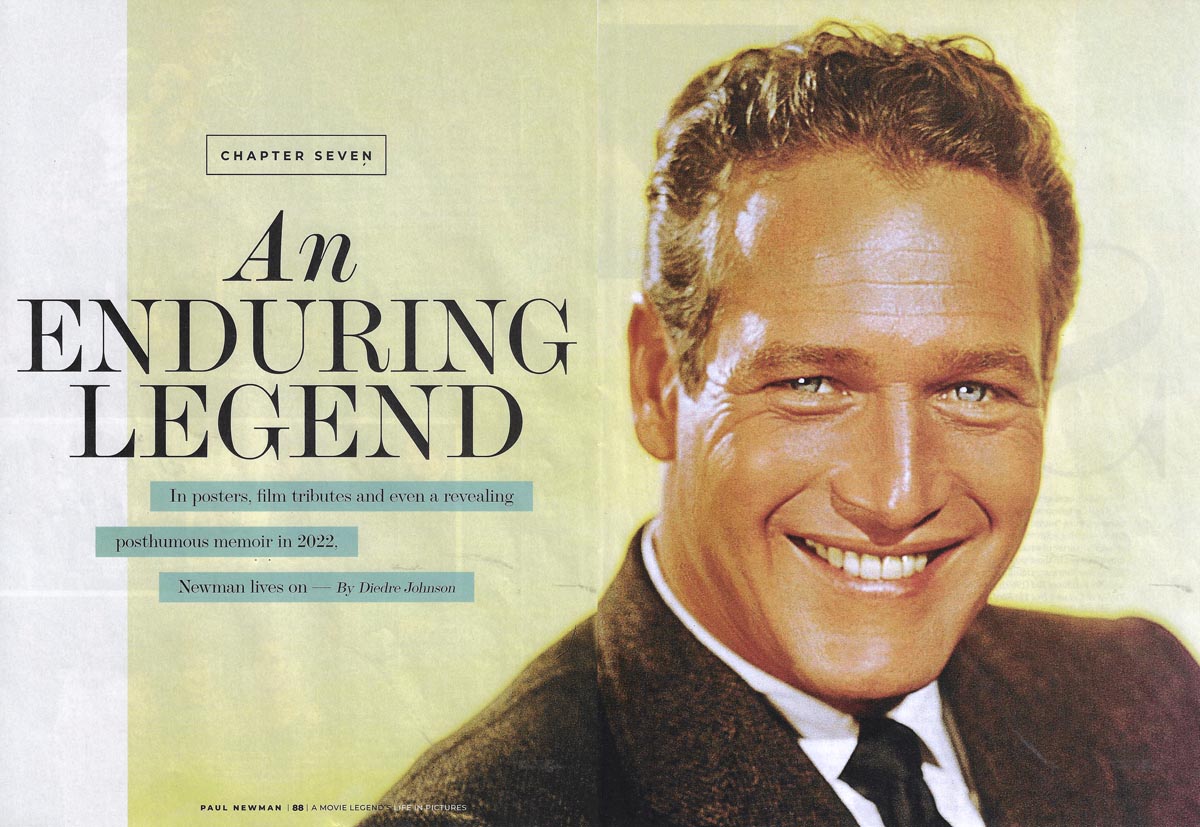

SOME OF THEM ARE TITLED SIMPLY, “PAUL NEWMAN Handsome, ung, ” while others are labeled, “Paul Newman, cigar,” “Paul Newman Joanne,” or “Paul Newman Vintage.” They could be film stills blown up to fill a wall, or converted ads for vintage luxury watches (the actor’s own Rolex Daytona timepiece sold for $17.8 million at auction in 2017). But with a Paul Newman poster, not much else needs to be said: Once you see that handsome man with a boy’s petulant lips and those piercing, pale-blue eyes, you already know who it is — and the stories you want those posters to tell you. As his wife, Joanne Woodward, once cracked to the press, “He’s got a pretty face, so maybe he’ll make it.”

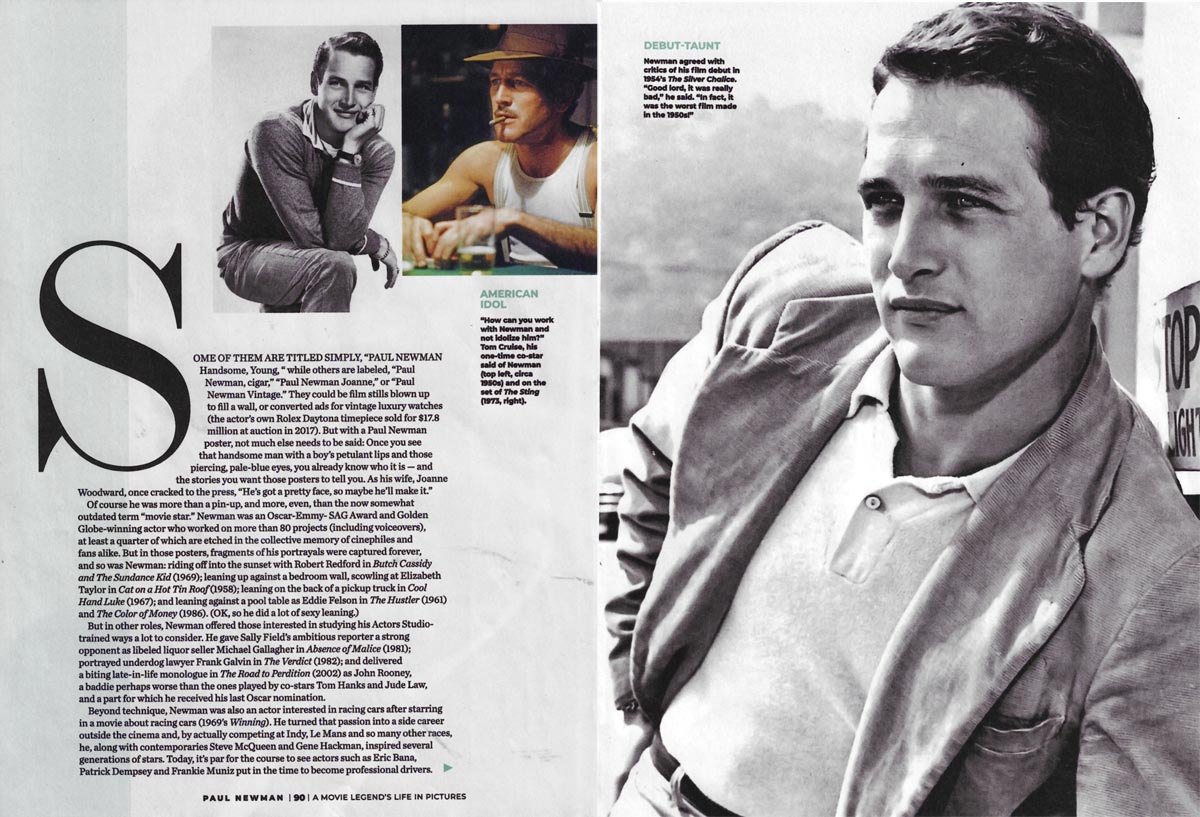

Of course, he was more than a pin-up, and more, even, than the now somewhat outdated term “movie star.” Newman was an Oscar-Emmy- SAG Award and Golden Globe-winning actor who worked on more than 80 projects (including voiceovers), at least a quarter of which are etched in the collective memory of cinephiles and fans alike. But in those posters, fragments of his portrayals were captured forever, and so was Newman: riding off into the sunset with Robert Redford in Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid (1969); leaning up against a bedroom wall, scowling at Elizabeth Taylor in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof(1958); leaning on the back of a pickup truck in Cool Hand Luke (1967); and leaning against a pool table as Eddie Felson in The Hustler (1961) and The Color of Money (1986). (OK, so he did a lot of sexy leaning.)

But in other roles, Newman offered those interested in studying his Actors Studio- trained ways a lot to consider. He gave Sally Field’s ambitious reporter a strong opponent as libeled liquor seller Michael Gallagher in Absence of Malice (1981); portrayed underdog lawyer Frank Galvin in The Verdict (1982); and delivered a biting late-in-life monologue in The Road to Perdition (2002) as John Rooney, a baddie perhaps worse than the ones played by co-stars Tom Hanks and Jude Law, and a part for which he received his last Oscar nomination.

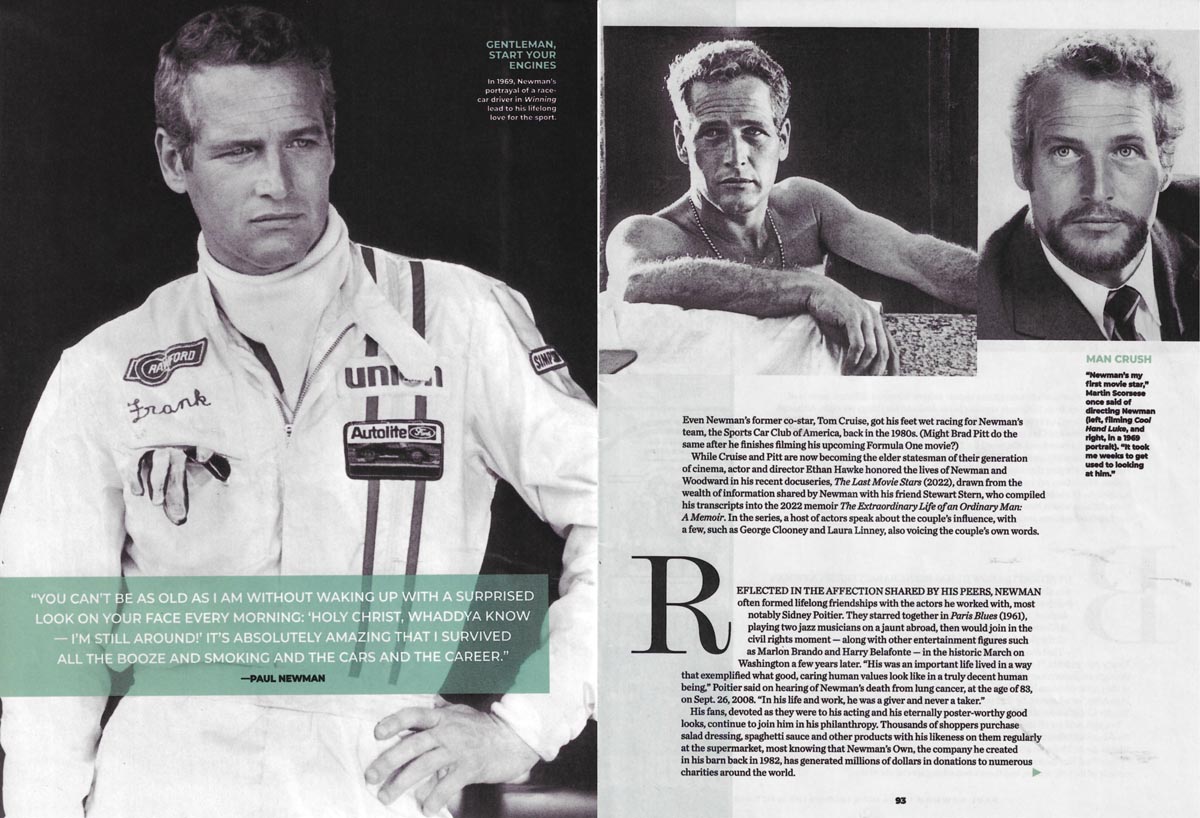

Beyond technique, Newman was also an actor interested in racing cars after starring in a movie about racing cars (1969’s Winning). He turned that passion into a side career outside the cinema and, by actually competing at Indy, Le Mans and so many other races, he, along with contemporaries Steve McQueen and Gene Hackman, inspired several generations of stars. Today, it’s par for the course to see actors such as Eric Bana, Patrick Dempsey and Frankie Muniz put in the time to become professional drivers.

Even Newman’s former co-star, Tom Cruise, got his feet wet racing for Newman’s team, the Sports Car Club of America, back in the 1980s. (Might Brad Pitt do the same after he finishes filming his upcoming Formula One movie?)

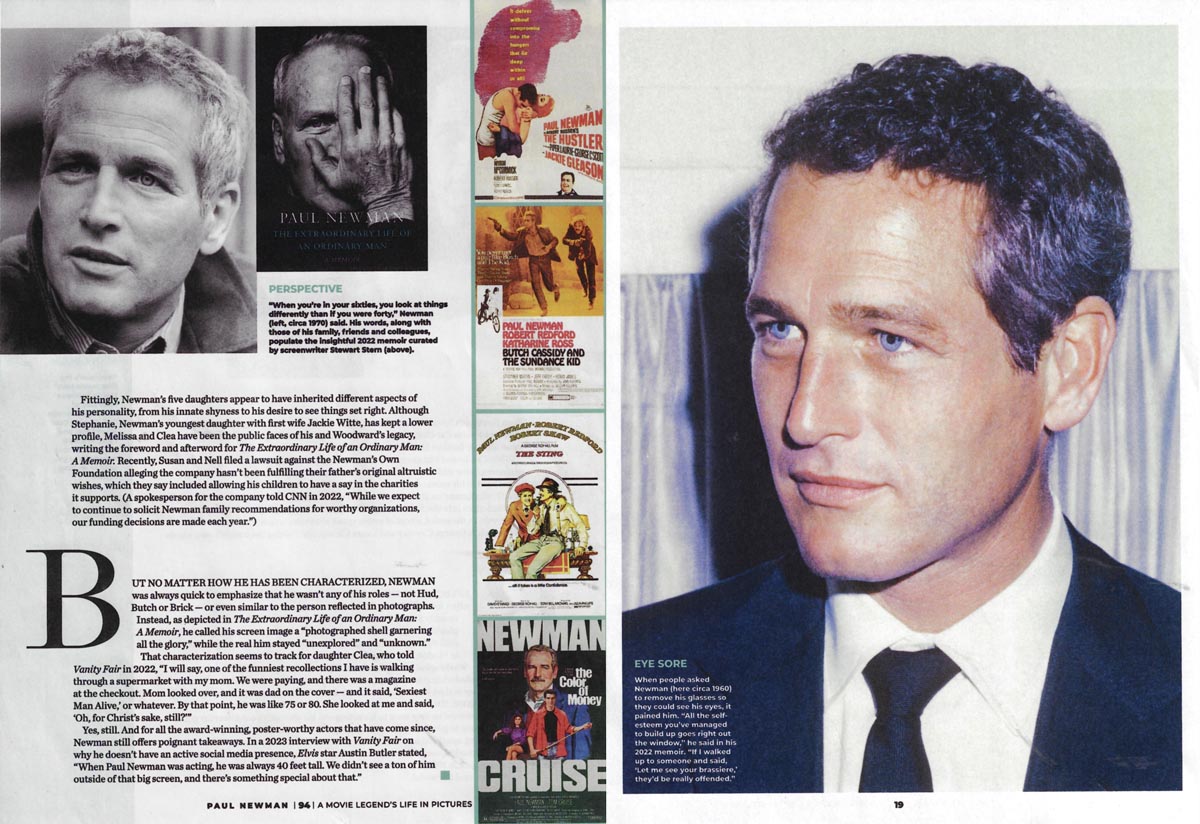

While Cruise and Pitt are now becoming the elder statesman of their generation of cinema, actor and director Ethan Hawke honored the lives of Newman and Woodward in his recent docuseries, The Last Movie Stars (2022), drawn from the wealth of information shared by Newman with his friend Stewart Stern, who compiled his transcripts into the 2022 memoir The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man: A Memoir. In the series, a host of actors speak about the couple’s influence, with a few, such as George Clooney and Laura Linney, also voicing the couple’s own words.

REFLECTED IN THE AFFECTION SHARED BY HIS PEERS, NEWMAN often formed lifelong friendships with the actors he worked with, most notably Sidney Poitier. They starred together in Paris Blues (1961), playing two jazz musicians on a jaunt abroad, then would join in the civil rights moment — along with other entertainment figures such as Marlon Brando and Harry Belafonte in the historic March on Washington a few years later. “His was an important life lived in a way that exemplified what good, caring human values look like in a truly decent human being,” Poitier said on hearing of Newman’s death from lung cancer, at the age of 83, on Sept. 26, 2008. “In his life and work, he was a giver and never a taker.”

His fans, devoted as they were to his acting and his eternally poster-worthy good looks, continue to join him in his philanthropy. Thousands of shoppers purchase salad dressing, spaghetti sauce and other products with his likeness on them regularly at the supermarket, most knowing that Newman’s Own, the company he created in his barn back in 1982, has generated millions of dollars in donations to numerous charities around the world.

Fittingly, Newman’s five daughters appear to have inherited different aspects of his personality, from his innate shyness to his desire to see things set right. Although Stephanie, Newman’s youngest daughter with first wife Jackie Witte, has kept a lower profile, Melissa and Clea have been the public faces of his and Woodward’s legacy, writing the foreword and afterword for The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man: A Memoir. Recently, Susan and Nell filed a lawsuit against the Newman’s Own Foundation alleging the company hasn’t been fulfilling their father’s original altruistic wishes, which they say included allowing his children to have a say in the charities it supports. (A spokesperson for the company told CNN in 2022, “While we expect to continue to solicit Newman family recommendations for worthy organizations, our funding decisions are made each year.”)

BUT NO MATTER HOW HE HAS BEEN CHARACTERIZED, NEWMAN was always quick to emphasize that he wasn’t any of his roles — not Hud, Butch or Brick — or even similar to the person reflected in photographs. Instead, as depicted in The Extraordinary Ide of an Ordinary Man: A Memoir, he called his screen image a “photographed shell garnering all the glory,” while the real him stayed “unexplored” and “unknown.” That characterization seems to track for daughter Clea, who told Vanity Fair in 2022, “I will say, one of the funniest recollections I have is walking through a supermarket with my mom. We were paying, and there was a magazine at the checkout. Mom looked over, and it was dad on the cover — and it said, ‘Sexiest Man Alive,’ or whatever. By that point, he was like 75 or 80. She looked at me and said, ‘Oh, for Christ’s sake, still?'”

Yes, still. And for all the award-winning, poster-worthy actors that have come since, Newman still offers poignant takeaways. In a 2023 interview with Vanity Fair on why he doesn’t have an active social media presence, Elvis star Austin Butler stated, “When Paul Newman was acting, he was always 40 feet tall. We didn’t see a ton of him outside of that big screen, and there’s something special about that.”